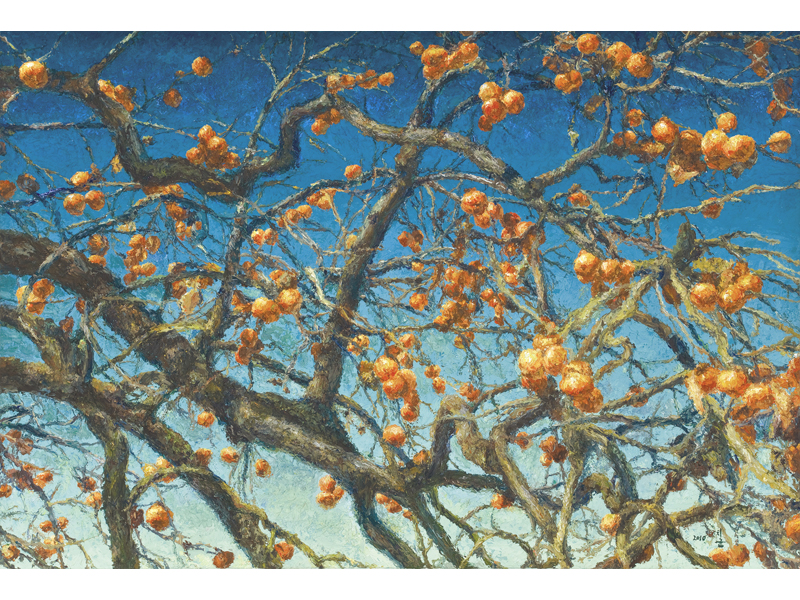

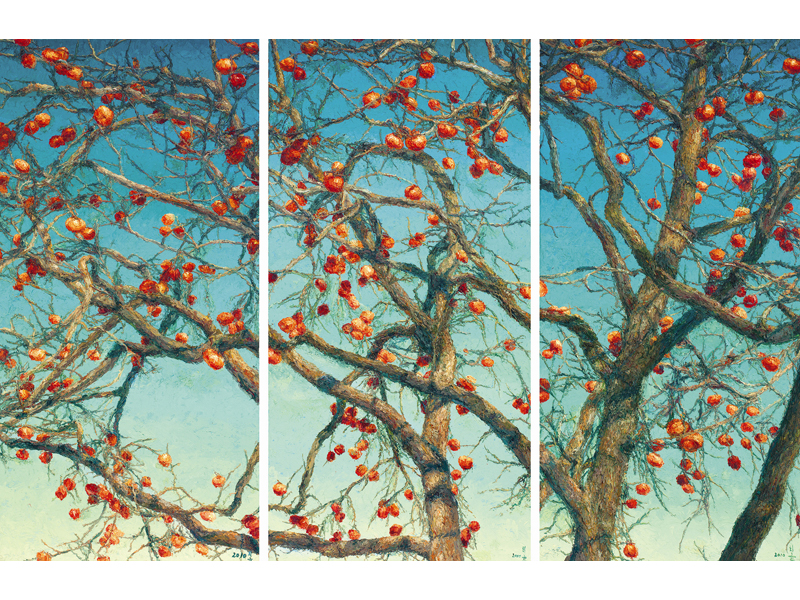

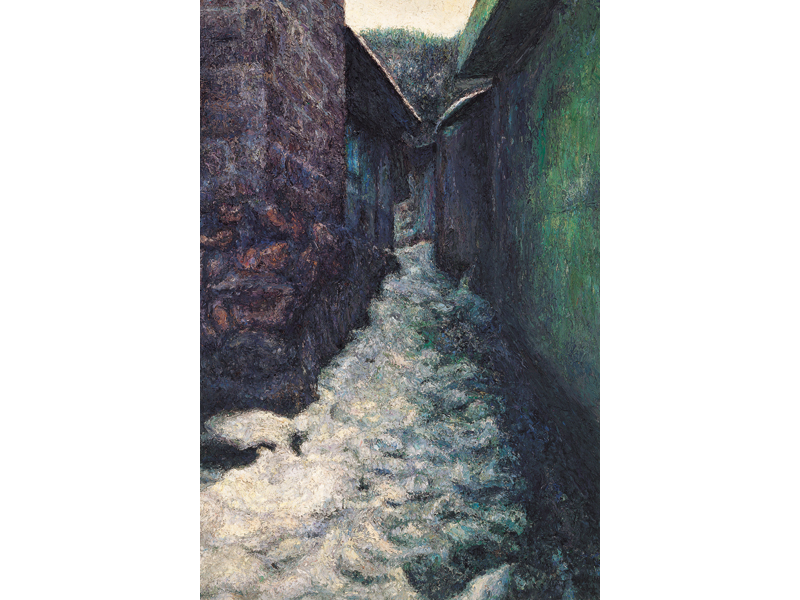

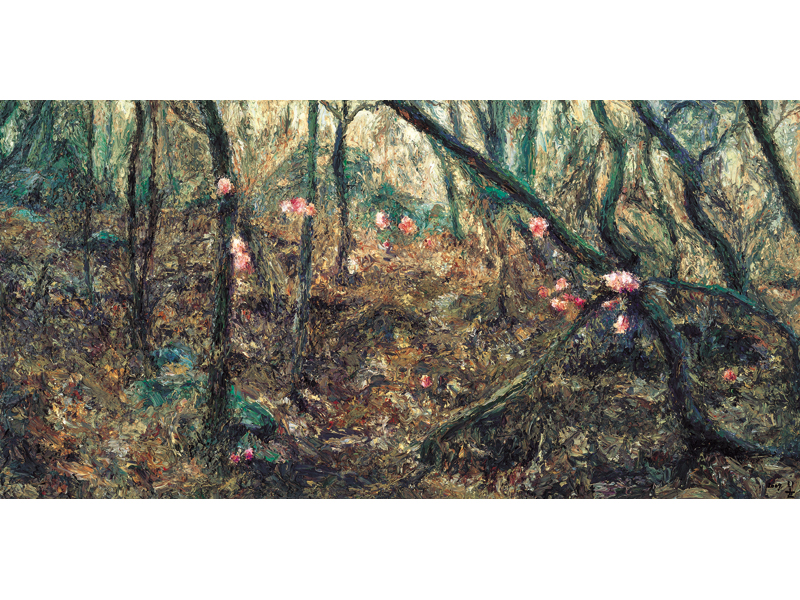

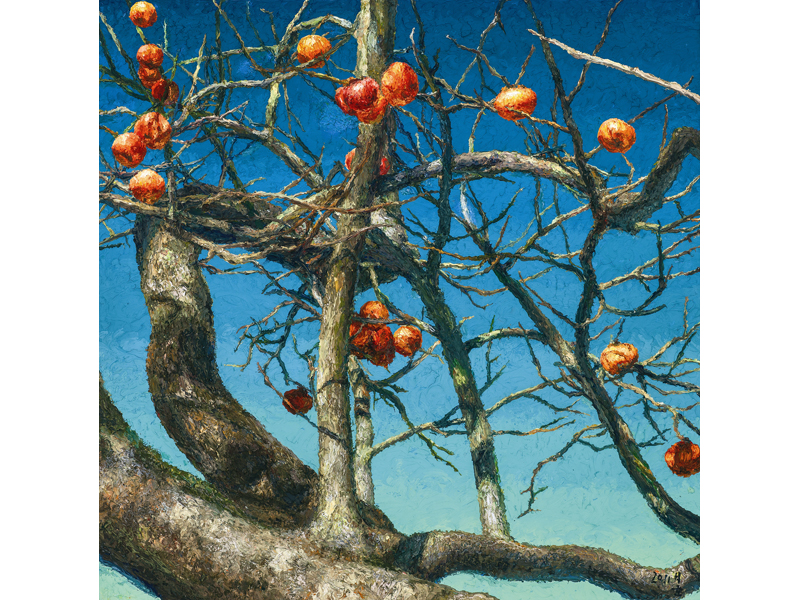

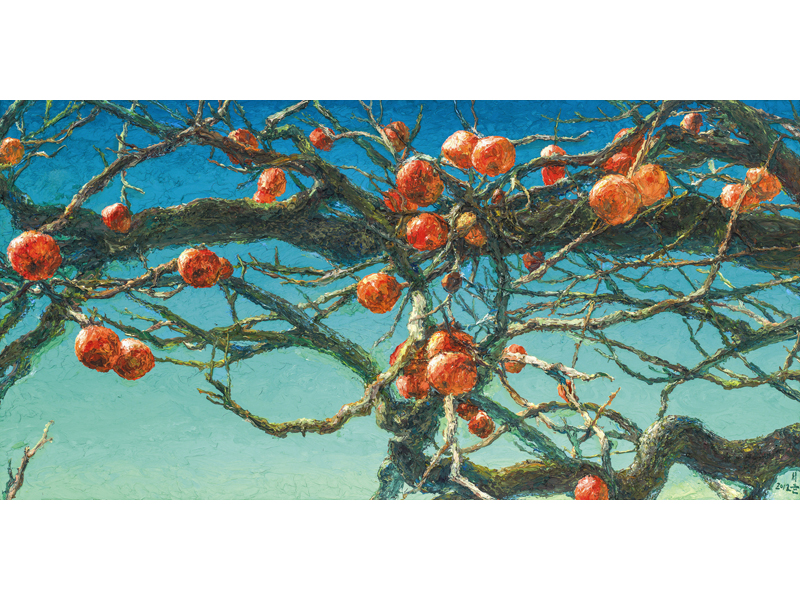

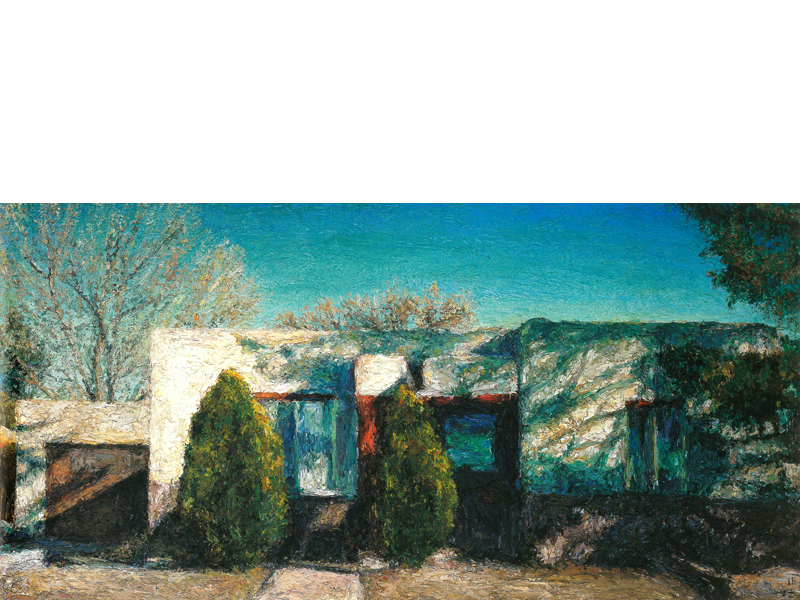

OH Chi-GyunPersimmons2010Acrylic on Canvas130.3 x 193.9 cmOH Chi-GyunPersimmons2010Acrylic on Canvas 160 x 80 cm (each) triptychOH Chi-GyunAlleyway of Winter2006Acrylic on Canvas131 x 87 cmOH Chi-GyunChanggyeonggung Palace 2007Acrylic on Canvas117 x 78 cmOH Chi-GyunThe Hill behind My Friend's House 2007Acrylic on Canvas117 x 78 cmOH Chi-GyunPersimmons2011Acrylic on Canvas110 x 110 cmOH Chi-GyunPersimmons2012Acrylic on Canvas60 x 120 cmOH Chi-GyunPersimmons2012Acrylic on Canvas78 x 116 cmOH Chi-GyunPersimmons2012Acrylic on Canvas100 x 200 cm

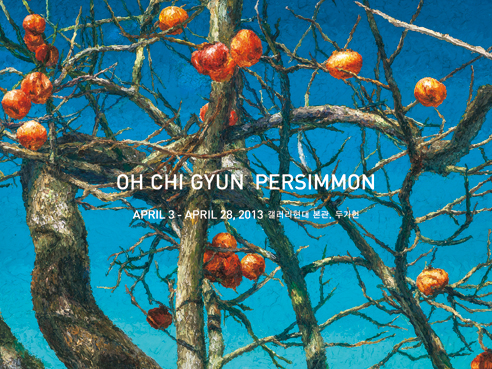

Related Exhibition

-

2013.4.3~4.28

-

2012.12.15~2013.1.31

-

2011.8.24~9.20

-

2010.1.12~2.10

-

2009.4.16~5.10

-

2008.8.16~10.10

-

2007.9.6~9.26